How to price your SaaS product

👋 Hello, I’m Lenny and welcome to a ✨ once-a-month-free-edition ✨ of my newsletter. Each week I humbly tackle reader questions about product, growth, working with humans, and anything else that’s stressing them out at the office.

If you’re not a paid subscriber, here’s what you missed this month:

Q: I'm building a SaaS product and don't know where to start when pricing it. How should I approach my pricing strategy?

When this question came in, I took to Twitter to find the smartest person in the world on SaaS pricing…

Many suggestions came though but one name came up again and again: @Patticus, aka Patrick Campbell.

I cold DM’d Patrick and asked him if he’d be up for writing a guest post. He instantly agreed 🙌🙌🙌

For those that don’t know Patrick, he is CEO of ProfitWell, and generally regarded guru on anything SaaS. Unrelated to this post, I started using ProfitWell a couple of months back to track my newsletter metrics, and the amount of insight you get into your subscription business is unreal. AND IT’S FREE. If you’re running a SaaS business, definitely check it out. This is not a sponsored post — I just love the product.

🚨 Bonus: Patrick Campbell is doing a live AMA at 5pm PT today (10/27) in our subscriber-only Slack group. Ask Patrick any question you have about pricing your product live!

With that out of the way, let’s dive in!

—

How to price your SaaS product

by Patrick Campbell

Pricing is one of those topics that sits at the nexus of uncomfortable and long-term, which means companies often don’t think about it for far too long. Even when they eventually figure it out, they don’t touch it again for years.

The most successful companies optimize monetization in some manner every quarter. You may be thinking, “they change their price every 3 months!?” No, and that's the first lesson of monetization: pricing goes so much further than the actual price. Let me explain.

If we go to a thirty thousand foot view, you have to think about what you're actually doing with pricing. No matter the business you're in — non-profit, retail, SaaS, DTC, B2B, whatever — you've created some sort of value. You attach a unit of measurement to the value you created: your price. Put simply, your price is the exchange rate on the value you're creating in the world.

But price doesn’t live in a vacuum. Everything in your business — from sales and marketing to product and finance — is used to drive someone to buy the product at the price you're offering. Dozens of aspects of your business influence your price, and how effectively it converts customers:

The segment and vertical you are targeting: You can go upmarket to customers who have higher willingness to pay, shift to a vertical that sees more value in your offering, or even change the ideal customer profile entirely.

Your product, positioning, and packaging: You can come out with new features, move features to different tiers, pull features out and make them add-ons, change up your value propositions, etc.

Your price: You can move your price up or down, which will impact conversion obviously, but will also impact the perception of your brand.

These are not the only axes when it comes to pricing, but the point is anything that influences the value of your product is involved in pricing and monetization. Cool – I've now given you a college lecture worthy of a tweed blazer, so let's dig into where you should start.

In the beginning, the actual number you're charging isn't that important.

There are some exceptions, but for the most part, you should first be figuring out the range you're in: a $10 product, $100 product, $1k product, etc. Don't waste time debating $500 vs. $505, because this doesn't matter as much until you have a stronger foundation beneath you.

What matters much more is two other questions:

Your value metric

Your ideal customer profiles and segments

These two elements are the foundation of your monetization and pricing strategy. Let’s explore them individually.

Step 1: Determine your Value Metric

A “value metric” is essentially what you charge for. For example: per seat, per 1,000 visits, per CPA, per GB used, per transaction, etc. If you get everything else wrong in pricing, but you get your value metric right, you'll do ok. It's that important. Partly because it bakes lower churn and higher expansion revenue into your monetization.

Pricing based on a value metric (vs. a tiered monthly fee) is important because it allows you to make sure you're not charging a large customer the same as you'd charge a small customer.

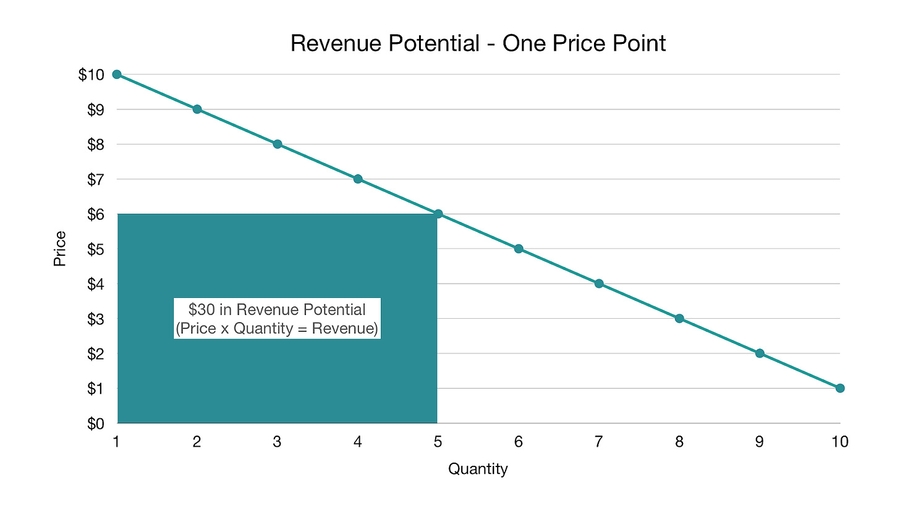

If you remember back to your high school or college economics class, the professor put a point on a demand curve for the perfect price and said “the revenue a firm gets is the area under that point.” The problem here is — what about all that other area under the curve? You’re missing out on that revenue by charging a flat monthly fee.

“Good, better, best” pricing is a bit more advantageous, because you end up with three points on our trusty demand curve, and thus more revenue potential. You see this in a lot of retail products who are constrained by being physical goods — the car with the basic package vs. the car with the stereo and sunroof vs. the car with everything. In software, it’s thankfully dying out, but you’ll still see it with mass-market products: Netflix, Adobe Creative Cloud, etc.

A value metric however allows you to have essentially infinite price points — maximizing your revenue potential. In practice, you’ll never show infinite price points on your pricing page, sales deck, or mobile conversion page, but you may have a customer come in at a certain level and then grow.

Value metrics also bake growth directly into how you charge because as usage or the amount of value received goes up (and those are not the same thing), the customer pays more. If they end up using or consuming less, they pay less (and thus avoid churning). This is why companies using value metrics are typically growing at double the rate with half the churn and 2x the expansion revenue when compared to companies that charge a flat fee or where the only difference between their pricing tiers are features.

How to determine your value metric

To determine your value metric, think about the ideal essence of value for your product — what value are you directly providing your customer?

In B2B, it's likely going to be money saved, revenue gained, time saved, etc. In DTC, it may be the joy you bring them, fitness achieved, increased efficiency, etc. Obviously, we can't measure all of these, but if you can, and your customer trusts your measurement (meaning you say you saved them $100 and they agree you saved them $100), that’s your value metric.

As an example, the perfect value metric for ProfitWell Retain (our churn recovery product) is how much churn we recover for you. We can measure this, and our customers agree to the measurement, so we can charge on that axis. Other pure value metric products include MainStreet, which handles government paperwork to automatically get you back tax credits — you pay a percentage of the money saved.

Most of you won't have a pure value metric, so the next step is to find a proxy for that metric. Take for example HubSpot’s marketing product. Their pure value metric is the amount of revenue their tool drives for your business. This is hard to measure and hard for the customer to agree to in terms of what percentage of credit HubSpot deserves for revenue from a blog post. Proxies for HubSpot are things like the number of contacts, number of visits, number of users, etc.

To find the right proxy metric, you want to come up with 5-10 proxies and then talk to your customers and prospects. You’ll typically find 1-2 of these pricing metrics will be most preferred amongst your target customers. You then want to make sure those 1-2 also make sense from a growth perspective. Your larger customers should be using/getting more of the metric, whereas your smaller customers should be using/getting less of the metric. You also want to make sure the metric encourages retention.

When we look at HubSpot, if they were to primarily price on “number of seats”, folks could share a login and HubSpot wouldn’t make much more money on large customers vs. small. Ironically they wouldn’t get as many people invested into HubSpot, because there’d be friction to adding additional seats. Instead, if they give unlimited seats and price based on “number of contacts” there’s minimal friction to getting as many people into HubSpot as possible to do activities (e.g. blog posts, email campaigns, landing pages, etc.) that then produce contacts.

The result: HubSpot’s marketing product’s value metric is “contacts”, which ensures growth is baked directly into how they make money. The usage drives the metric, which therein drives revenue. Most importantly customers small, medium, and large are all paying at the point they see value and then can grow.

Some other examples:

Wistia charges by the number of videos or channels you use/have

Zapier invented the concept of zap (connection of software) and charge based on time to connect

Husqvarna charges based on time for lawn care products vs. making you buy them

Rolls Royce charges per mile for airplane engines. They own the engines on the plane you own and do all the maintenance. Cool model.

Fresh Patch charges based on the amount of grass you want per month for your dog — yes they deliver grass to you monthly

As a side note, you should stop pricing based on seats for products where each seat doesn’t provide a unique experience. For instance, in a CRM if I log in to the AE sitting next to me’s account, I can’t really do my work because I’m only seeing their leads and accounts. Conversely, if I log in to our marketing manager’s account in HubSpot, I can do all the work I need. Thus, for the latter, seats is not the right value metric.

Per seat pricing is a relic of the perpetual license era when we couldn’t measure usage or value enough within our products. We’re beyond that point, so use the above as a good litmus test.

Step 2: Determine your customer profiles and segments

The second key component of your pricing strategy is determining your target segment and ideal customer profile. We've all heard about personas, and you may be rolling your eyes at the concept, but most personas are useless because they aren’t quantitative enough. When used properly, quantified personas and segments are beautiful tools. The information needs to go beyond just cute names like “Startup Steve," with a cute avatar, and cute meetings where people tell you they’re targeting "developers".

To get quantified personas, you need to pull out a spreadsheet. Here’s a template you can use.

1. Columns: Customer profiles you're targeting

These can take many forms, but the ultimate goal is to be as specific as possible so that you not only know who you’re targeting but how to monetize and retain them. Pragmatically, you typically separate these profiles based on size or role (or both). For example, a marketing automation product may target the following profiles:

Marketing leaders (Director and higher) at companies $1M to $10M

Marketing leaders (Director and higher) at companies $10.01M to $50M

Marketing leaders (Director and higher) at companies $50.01M to $100M

The point is you can’t be everything to all people and you need to understand who you’re targeting in order to make better decisions.

2. Rows: Characteristics of each profile to help you differentiate between them

Most valued features

Least valued features

Willingness to pay

Lifetime value (LTV)

Customer acquisition costs (CAC)

…and any other metric or category you think could be useful

If you're just starting out or you don't have some of this data, it’s fine. Still fill it out though with your hypotheses. You know something about your customers.

Next, you then need to validate (or invalidate) the most pressing hypothesis in that spreadsheet based on the decisions you’re going to make. If you're going to validate a new feature for a particular segment, then that's where you should start. Price point the biggest question? Start by researching the price point with each of these roles/segments.

If you don't know who your key roles/segments are, there's no way in hell you’ll set up an efficient growth flywheel, let alone an optimized pricing strategy. Personas act as a constitution within your business to centralize your focus and arguments about direction.

If you don't do segment and persona analysis, you better be able to raise a ton of money. I guarantee you there's some persona or segment on some vision document or in that euphoric part of your entrepreneurial brain that is completely wrong for your business. I see it all the time. Even I — someone who thinks about segments and customer research all the time — fall prey to being an absolute idiot with who we should target.

When we built ProfitWell Metrics (our free subscription metrics tool) I thought we were geniuses who were going to be billionaires. Turns out analytics products are terrible. Willingness to pay for them is terrible; retention for them is terrible; NPS is terrible. Everything is just terrible, mainly because customers don't appreciate graphs or at least aren't willing to pay much for them. When we did our research this became obvious and put us 18 months ahead of our competitors, pushing us to change up the positioning of the product to freemium, which has fueled our business ever since (oh and our NPS is 70, because we massively over-deliver a free product better than the paid competition).

Never underestimate the power of focusing on the customer through research. You should never, ever just do what they ask, but you need to be an anthropologist who knows them better than anyone else.

Step 3: User research + experimentation

Beyond your value metric and core segments, the monetization game becomes extremely tactical and research-based. Figuring out your price point involves researching those segments and then making decisions in the field. Same with discounting, add-on, and packaging strategies. The point: monetization is never finished because it’s the very essence of translating your value into an optimal framework for your target customer segments.

Practically this is why you should be experimenting with your monetization every quarter. Experimentation can get tricky and have a few quirks, but you’ll find it’s similar to most growth frameworks out there (which are all versions of the scientific method).

Here’s a good prioritization list of what you should attack in optimizing your monetization strategy once you have your core segments and value metric figured out:

Priority 1: Foundational [See above]

Core customer segments

Value metrics

Priority 2: Core

Order of magnitude price point (are you a $10 product vs. a $500 product)

Positioning and value props

Packaging

Priority 3: Optimizations

Add-on strategy

Specific price point (are you a $10 product vs. a $11 product)

Price localization/internationalization

Discounting strategy

Contract Term optimization

Priority 4: Growth accelerators

Freemium

Market expansion (going up or down market)

Vertical expansion

Multi-Product

Your true order of operations with monetization will vary, but for the most part, all companies should work through the foundational and core sections before moving to the optimizations and growth accelerators. If you’re larger or there’s a fire, you may start with an optimization. In fact, this is sometimes a good idea. Something more scoped like “price localization” can help get momentum, be a forcing function to clean up tech and experimentation stacks, and mitigate political conversations. Remember, monetization is something that’s important, uncomfortable, and something you likely don’t know much about, so progress is better than nothing. Start small. You can (and should) always do more.

Well, this is already longer than Lenny wanted, so I’m going to lean into the length with two last thoughts:

I’ve included a rapid-fire of data that guides common monetization questions below.

If you ever have a question about pricing or subscription benchmarks in general hit me up at patrick@profitwell.com or @Patticus on Twitter.

🚨 Reminder: Patrick Campbell is doing a live AMA at 5pm PT 10/27 in our subscriber-only Slack group. Ask Patrick any question you have about pricing your product, live!

Rapid-fire bonus advice ⚡

1. You should localize your pricing to the currency and willingness to pay of the prospect's region

Revenue per customer is 30% higher when you just use the proper currency symbol

Having different price points in different regions increases revenue per customer further, and is justified based on different demand environments in different regions

2. Freemium is an acquisition model, not a part of pricing

Think of freemium as a premium e-book driving leads, not another pricing tier

Don't do freemium until you truly understand how to convert leads to customers, because you’ll end up increasing noise or false positives when you’re trying to figure out your segment beachheads. The best folks who deploy free typically don’t implement freemium until 2-3 years into their business. The exceptions to this notion are if you have a very specific need or network effect (eg. marketplaces, social networks, etc.) or if you have a top 50 growth person on your team.

To be clear, I'm not saying DON’T do freemium. I'm saying it's a scalpel, not a sledgehammer that requires thought. A lot of people end up reading our articles on freemium and end up going, “cool, let’s do freemium and we’ll be a unicorn.” I’m being pragmatic in that you need to realize freemium is fantastic, but doing freemium properly takes a lot of effort and nuance.

Paid users who convert from free tend to have higher NPS, better retention, and much lower CAC.

3. Value propositions matter oh so much

In B2B value propositions can swing willingness to pay ±20%, in DTC it's ±15%

4. Don't discount over 20%

In some verticals discounting over 20% may be fine, but you're likely not in one of them (although you may think you are), but the size of the discount almost perfectly correlates with higher churn. Large discounts get people to convert, but they don't stick around.

5. For upgrades to annual discounts don't use percentages and try offers

Percentages don't work as well as whole dollar amounts for discounts (ie. "1 month" will work better than "X percent off"). Annuals see much lower churn rates.

6. Should you end your price in 9s or 0s? Depends on your price point

Ending your prices in 9s evokes a discount brand, making the customer feel like they're getting something. Ending in 0 evokes luxury or premium. Studies on this for technology products is inconclusive. We have seen it increase conversion in lower priced products, but retention isn't as good with those customers.

7. You should experiment with your pricing in some manner every quarter

This doesn't mean change the price point each quarter, but experiment with something. More changes correlates with increasing revenue per customer. Like all things, focusing on something makes you improve it.

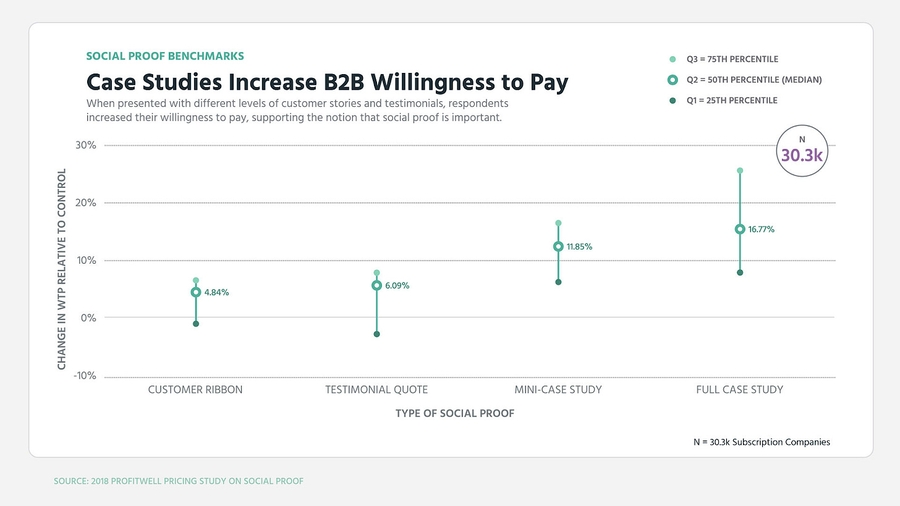

8. Case studies boost willingness to pay quite a bit

Social proof is important. Case studies can boost willingness to pay by 10-15% in both B2B and in DTC

9. Design helps boost willingness to pay by 20%

This graph didn't look this way 10 years ago when design didn't do much for willingness to pay. Today, affinity for a company's design can boost willingness to pay considerably.

10. Integrations boost retention and willingness to pay

The more integrations a customer is using, typically the higher their willingness to pay and the better their retention. I wouldn't charge for the integrations, but I'd use this as a tool to get people hooked in and paying more or buying different add-ons.

Still here? Ok, I think I've overstayed my welcome at this point. If you ever have any questions about pricing, retention, or subscription benchmarks, hit me up on Twitter.

Our growth team would also be upset with me if I didn't point out you can get all of your subscription financial metrics by hooking up your billing system to ProfitWell in two minutes (yes, even with Zuora). We're used by over 20k subscription companies ranging from the Fortune 50 to johnny and jane startups. Oh, and it's free. :)

—

Thank you Patrick for sharing your wisdom 🙏🙏🙏

If you have any questions or further suggestions, leave a comment!

🔥 Job opportunities

Product: Cerebral, ClassDojo, KUDO, Hipcamp, Product Hunt

Growth: Coda, Instrumentl, Levels, Shef, Wren

Design: Pachama, Office Hours, Runway, Stytch, Watershed

Engineering manager: Cerebral

Backend engineer: Coda, Sourcetable

Is there anyone in your life who would benefit from this newsletter or community? Consider giving them a gift subscription 💞

Sincerely,

Lenny 👋