How the biggest consumer apps got their first 1,000 users

Hello, and welcome to a free monthly edition of my newsletter. I’m Lenny, and each week I tackle reader questions about product, growth, working with humans, and anything else that’s stressing you out at the office. Send me your questions and in return, I’ll humbly offer actionable real-talk advice. 🤜🤛

If you find this post valuable, check out some of my other posts:

To receive this newsletter in your inbox weekly, consider subscribing 👇

Q: How did the big consumer apps get their first 1,000 users?

Considering every startup confronts this question at some point, I was surprised by how little has been written about it. Particularly anything actionable. So I decided to do my own digging. I spent the past month personally reaching out to founders, scouring interviews, and tapping the Twitterverse. Below, you’ll find first-hand accounts of how essentially every major consumer app acquired their earliest users, including lessons from Tinder, Uber, Superhuman, TikTok, Product Hunt, Netflix, and many more. Enjoy!

My biggest takeaways from this research:

Just seven strategies account for every consumer apps’ early growth.

Most startups found their early users from just a single strategy. A few like Product Hunt and Pinterest found success using a handful. No one found success from more than three.

The most popular strategies involve going to your user directly — online, offline, and through friends. Doing things that don’t scale.

To execute on any of these strategies, it’s important to first narrowly define your target user. Andy Johns recently shared some great advice about this.

The tactics that you use to get your first 1,000 users are very different from your next 10,000. A topic for a different post.

If you have any additional insights, stories, or feedback to share, don’t hesitate to DM me. Otherwise, let’s dive into the strategies.

1. Go where your target users are, offline

Key question: Who are your early target users, and where they currently congregating offline?

College campuses — Tinder and DoorDash

Whitney Wolfe and Justin Mateen would basically run around USC pitching Tinder to sororities and fraternities. The hook of seeing other single people on campus for the first time (and knowing if they’re interested in you) went viral.

The very first iteration of DoorDash was a website called paloaltodelivery.com with PDF'd menus of restaurants in Palo Alto. Tony and the team printed a bunch of flyers charging $6 for delivery and put them all over Stanford University. He and the team first wanted to see if there was demand. That was how it all started. A website with PDF menus and flyers.

Startup offices and transit hubs — Lyft and Uber

We asked everyone on our team to give us their list of contacts at startups and we contacted them to ask their permission to come by with a free Bi-Rite ice cream sundae dropoff for their employees. They basically all said yes, because Bi-Rite is delicious. :) So we arranged a dropoff operation and had teams of staff with insulated bags taking ice cream sundae kits to all of the companies and giving them Lyft credits.

There was a very significant use of street teams early on at Uber. They went to places like the Caltrain station and handed out referral codes. There are stories about how Travis went to Twitter HQ personally and handed out referral codes.

Malls — Snapchat

Evan started showing it to people one on one, giving tutorials, explaining why it was fun, even downloading the app for them. […]

Evan was willing to try anything to get users. When he was home in Pacific Palisades, he would go to the shopping mall and hand out flyers advertising Snapchat. “I would walk up to people and say, ‘Hey would you like to send a disappearing picture?’ and they would say, ‘No,’” Evan later recalled.

— How to Turn Down a Billion Dollars, The Snapchat Story by Billy Gallagher

Neighborhood HOAs — Nextdoor

Back then, the founding team knew that it would only work if they could find a neighborhood to embrace the idea of a social network for neighborhoods, as well as test it along the way. Choosing the right neighborhood was essential.

That neighborhood is known as Lorelei. Nestled close to the Bay on streets shaded by trees, the neighborhood was close-knit and small yet vibrant, with the longest-standing homeowner’s association in the state of California. The community already had some ways to communicate with each other, which was a promising sign. We reached out to board members of the homeowners association, and they were more than willing to hear us out. After an initial conversation, they invited us to present the concept to more residents at their next board meeting.

Craft fairs — Etsy

Etsy decided to actually go into all these fairs across the United States, having people travel to all these craft fairs and recruit sellers because the sellers would eventually recruit their own buyers to the website instead of just using digital marketing.

Apple stores — Pinterest

We did all kinds of pretty desperate things, honestly. I used to walk by the Apple store on the way home. I’d go in and change all the computers to say Pinterest. Then just kind of stand in the back and be like, “Wow, this Pinterest thing, it’s really blowing up.”

(Note: This strategy will obviously be less effective while we shelter-in-place 😷)

2. Go where your target users are, online

Key question: Who are your early target users, and where they currently congregating online?

Hacker News — Dropbox

Drew created a simple video, demoing the product, and published it on April 2007 on Hacker News with the title "My YC app: Dropbox – Throw away your USB drive. That video brought the first users to the emerging Dropbox.

App Store — TikTok/Musical.ly

There was a secret in the app store. You could make the application name really really long. And the search engine on the App Store gives more weight to the application name rather than the keybookwords defined. So we put a really long application name, "make awesome music videos with all kinds of effects for Instagram, Facebook, Messenger”. And then traffic came from the search engine. That's how we initially got started.

— Alex Zhu

ProductHunt — Loom

First ~3k came in from Product Hunt on launch day + 1-2 days after.

3k-20k: Came from early champions at organizations (we tried to build 1:1 relationships with all of them).

21k+: we introduced our referral system ($5 in credits for every coworker you refer up to $50)

Piggy-back off of an existing online community — Netflix and Buffer

To help us connect further with customers, we brought in Corey Bridges to work on customer acquisition – or, more specifically, on something we jokingly called Black ops. A one-time English major at Berkely, he was a brilliant writer with a gift for creating characters.

He'd realized, early on, that the only way to find DVD owners was in the fringe communities of the internet: user groups, bulletin boards, web forums, and all of the other digital watering holes where enthusiasts met up. Corey's plan was to infiltrate these communities. He wouldn't announce himself as a Netflix employee. Posing as a home theater enthusiast or cinephile, he would join the conversation in communities geared toward DVD fanatics and movie buffs, befriend the major players, and slowly, over time, alert the most respected commenters, moderators, and website owners about this great new site called Netflix. We were months from launch, but he was planting seeds that would pay off...big time.

— That Will Never Work by Marc Randolph (Netflix)

Solely through guest blogging we’ve acquired around 100,000 users within the first 9 months of running Buffer. Here is more on this number, a bit before we hit the 100,000. It’s been something that was very gradual though. Within the space of around 9 months, I wrote around 150 guest posts. Of course the early ones barely drove any traffic and only very gradually did things improve, I think that’s very important to understand. It will take a while until you can find the right frequency of posting.

— Leo Widrich (Buffer)

3. Invite your friends

Key question: Do your friends fit into the target user group? If so, have you invited them yet?

Yelp

Inviting people from our network (mostly former coworkers from PayPal) drove our initial users. We asked all our network to invite their friends, and being startup people who wanted to help us, they obliged, so two-degrees out we probably got to 1k or so users. The takeaway is not to underestimate the power of one's personal referral network and to think deeply about the incentive and mechanics.

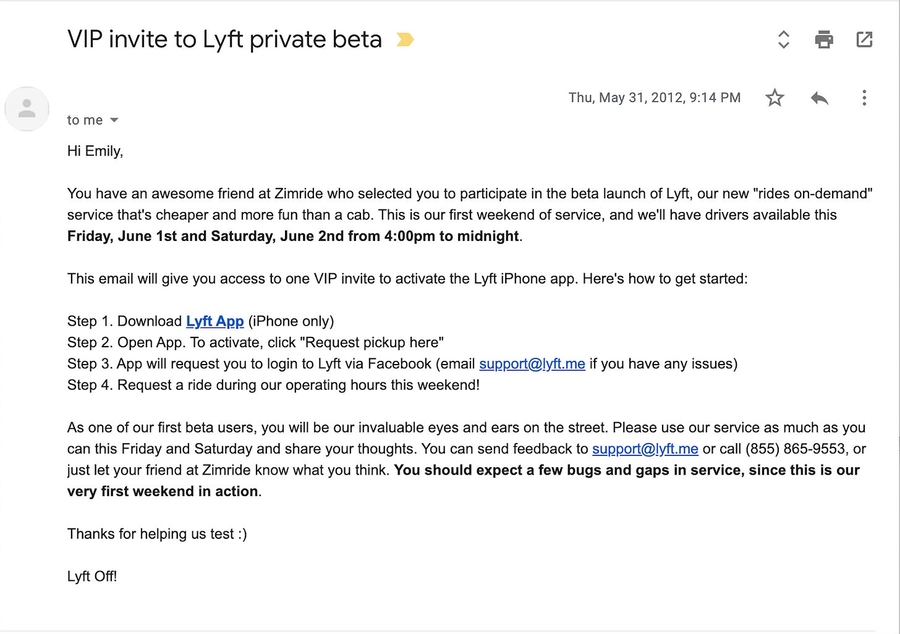

Lyft

Before the waitlists came personal email invites to our friends, like the one above.

Facebook

Thefacebook.com went up on Wednesday, February 4, 2004. “It was a normal night in the dorm,” Moskovitz recalled. “When Mark finished the site, we told a couple of friends. And then one of them suggested putting it on the Kirkland House online mailing list, which was, like, three hundred people. And, once they did that, several dozen people joined, and then they were telling people at the other houses. By the end of the night, we were, like, actively watching the registration process. Within twenty-four hours, we had somewhere between twelve hundred and fifteen hundred registrants.”

Quora

Quora launched in January 2010 with a user base largely composed of D'Angelo's and Cheever's college and high-school friends, meaning there was a lot of early Quora information on the best places to eat in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where Cheever was raised. But they also built a feature into the site whereby users could invite people, and soon their friends from Facebook were summoning people from other startups, and other entrepreneurs.

— Wired

LinkedIn

Reid intentionally seeded the product with successful friends and connections recognizing that cultivating an aspirational brand was crucial to drive mainstream adoption. (The entire company would have been doomed if there had been massive adoption of have-nots, instead of people who were hiring, recruiting etc.)

Slack

We begged and cajoled our friends at other companies to try it out and give us feedback. We had maybe six to ten companies to start with that we found this way.

The pattern was to share Slack with progressively larger groups. We amplified the feedback we got at each stage by adding more teams.

Pinterest

So we released the app and I did probably what everyone does–emailed all my friends and kind of hoped that it would to take off. And no one really got it, to be totally honest with you. […] But there was a small group of people that were enjoying it. And those folks were not who I think stereotypically you think of when you think about early adopters. They were folks that I grew up with, people that were using it for regular stuff in their life. You know, “What is my house going to look like? What kind of food do I want to eat?” Things like that.

4. Create FOMO in order to drive word-of-mouth

Key questions:

Does your product rely on UGC? Consider curating the early community.

Is your value-prop incredibly strong? Consider throwing up a waitlist.

Is your product innately social? Consider relying on existing users to invite new users.

Make it exclusive by curating the early community — Instagram, Pinterest, and Clubhouse

It’s been interesting to watch Clubhouse do this via private Testflight:

Curation (keeping quality high)

Exclusivity (creates FOMO)

Quick iteration (no App Store review process)

High-quality referrals from initial seed users

I think the biggest thing overall was that as we were prototyping and testing [Instagram] we gave it to a few folks who had very large Twitter following. Not necessarily a large following overall, but very large followings within a specific community — specifically, the designer community, the online web design community. We felt that photography and the visual element of what we were doing really resonated with those people. And we gave it to those specific people who a large followings.

And because they shared to Twitter, it created this tension, of like “When is this thing launching, when’d do I get to play with it?” and that’s the day when we actually launched, it had that springboard affect.

— Kevin Systrom (Instagram)

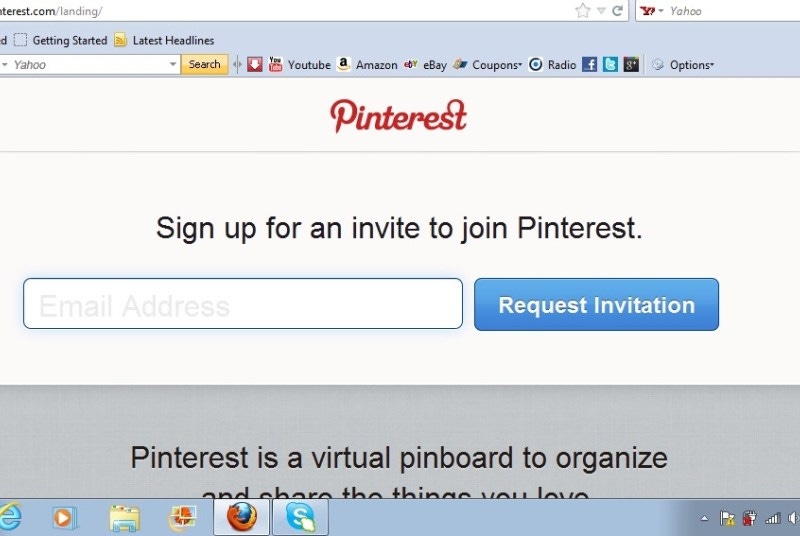

Pinterest started as an invite-only community. The first users were design bloggers Silbermann recruited. He advised these invitees to only extend admission to people they knew with unique ideas and creative minds. The exclusive community grew slowly until 2012 when the site removed the invitation requirement.

Add a waitlist - Mailbox, Robinhood, Clubhouse, Superhuman, and Pinterest

Mailbox, the email inbox management app for iPhone that was released in beta this week, currently has around 700,000 users queuing up for access, at the time of this writing […] It’s ostensibly a mechanism to help Mailbox’s servers manage the tremendous demand put upon them by users, though some believe it’s a marketing ploy designed to increase demand.

In the first year of Superhuman, as we were primarily building, we threw up a landing page. It was a terrible landing page, a basic Squarespace thing, that took us all of 2 hours to put together. All you could do on this page was throw in your email address. And when you threw in your email address, you got an automatic email from me, with two questions:

What do you use for email today?

What were your pet peeves about it?

The last thing from our minds when we launched Robinhood, the initial website, was that it would blow up overnight, so we were kind of cavalier in the way we approached it.

[The website] had a description in very simple language saying, "Commission-free trading, stop paying up to $10 per trade." And then there was a button that let you sign up, and then when you signed up, you put in your email, and you would join this wait list where we would actually show you: There's this many people ahead of you, this many people behind you. […]

I remember distinctly it was a Friday night. We had been working on the wait list in preparation for our press launch, which would have been, I think, the following Wednesday or Thursday. Everyone goes home, and I wake up Saturday morning, and I open up Google Analytics, and I see something like 600 concurrents on our site, which nobody knew about at that point. I was just like, "What's going on? This is not normal. Something must be wrong." Right?

And I'm looking at the analytics — I see a lot of traffic, or the majority of it, coming from Hacker News. And I open up Hacker News, and I see No. 1: "Chinese Land Spaceship on the Moon," No. 2: "Google acquires Boston Dynamics, the Robotics Company," and No. 3 was: "Robinhood: Free Stock Trading." So, first of all, I was like, "Oh man, like No. 3 on Hacker News? This is sort of like every engineer's dream in the Valley, right?

New users must be invited by existing users - Spotify

The music streaming service went live in October 2008, and it kept its free service invitation only, something that had been in place whilst it was in the final stages of development prior to public launch.

The invitation-only element was a vital part of the platform’s rise. Not only did it help manage the growth level of Spotify, but it also helped create a viral element to the service, with users each having 5 invites at first to share with their friends.

— TNW

5. Leverage influencers

Key question: Who are influencers of your target users, and how could you get them to talk about your product?

Twitter

This is the day-by-day chart for the initial launch. The first public mention of the service I can find is on Evan William's blog late on July 13th, but you can see that even on the 12th there was a mini-boom in registrations. Then Om Malik's post on the 15th really pushed it over the top, with more than 250 people signing up the next day. What I find fascinating is that there were less than 600 people on the service at that point, so it was a very prescient plug. […]

A recurring theme is the power of that initial publicity in driving the early users, and the feeling that it was a way to connect with an interesting group of people. Evan's high-profile and Om's endorsement must have been a big help in building that sort of buzz.

Product Hunt

Once we identified an influencer, Nathan or myself sent a personal email, inviting them to contribute and linking to the PandoDaily or Fast Company articles, to tell our story. A manual process indeed, but an effective way to recruit good contributors and open lines of communication for future feedback.

Instagram

The founders picked their first users carefully, courting people who would be good photographers—especially designers who had high Twitter follower counts. Those first users would help set the right artistic tone, creating good content for everyone else to look at, in what was essentially the first-ever Instagram influencer campaign, years before that would become a concept.

Dorsey became their best salesman. He was initially shocked to find out his investment money was going toward an entirely different app than Burbn. Usually, founders pivoted to a new product as a last-ditch effort to avoid going out of business. But Dorsey loved Instagram, way more than he’d ever loved Burbn.

When Instagram launched to the public on October 6, 2010, it immediately went viral thanks to shares from people like Dorsey. It reached number one in camera applications in the Apple app store.

— No Filter: The Inside Story of Instagram, by Sarah Frier

6. Get press

Key question: What’s a unique, compelling, fresh story you could pitch press?

Superhuman

The best way to do it is to pick one or two events a year where you can insert yourself into the cultural zeitgeist. For us, one such event was when Mailbox was being shut down. It was the perfect narrative, “I’m over here, come look at my company.” […] I currently have one of the most widely read articles on how to survive an acquisition. It was written in response to the Mailbox shutdown. […] That post ended up on Medium, and was syndicated to qz.com. We were able to insert it into the Zeitgeist. That article probably took me three days of doing nothing else, and another day of shopping it around. So four days all in. But those four days bought north of 5,000 signups.

Product Hunt

I wrote guest posts on tech publications (like this article on FastCo) to drive awareness. In the early days, press was effective in driving adoption. The same people that read tech publications like TechCrunch are the same people that might want to visit Product Hunt. Additionally, we forwarded compelling products that launched on Product Hunt to reporters that I knew. I made sure to send products that were relevant to their interests or beat, resulting in several articles mentioning and linking back to Product Hunt. Bonus points: We were helping makers and early stage startups get more visibility

Airbnb

The event that marked the turning point in the business was the 2008 Democratic National Convention (DNC) in Denver, Colorado. The pair saw an opportunity to capitalize on the quadruple over-attended event that caused a massive shortage in rental housing. Finding hosts to offer up rooms in their houses was actually the easy part. Getting people to rent those rooms proved more difficult.

The first counterintuitive strategy was to pitch only the bloggers with the smallest audience possible. […] As ridiculous as it sounds, the coverage by these bottom-feeder press was the social proof that more prominent publications needed to piggyback on the story. Eventually, national news networks, including NBC and CBS, were interviewing the founders of the unknown startup that was housing the biggest political convention in history.

The DNC bump was great for business, but it only lasted a week. The founders were desperate for a way to extend the impact of the event. While sitting around their kitchen table one day, still extremely broke, they came up with the idea that would bring Airbnb to profitability: cereal.

Both designers who graduated from the prestigious Rhode Island School of Design, the pair created fictitious cereals called “Obama O's, the Cereal of Change,” and “Cap’n McCain's, a Maverick in Every Box.” They designed the box artwork themselves and convinced a student at UC Berkeley to print 500 units of each box on the cheap. The boxes were delivered as flat rectangles that had to be cut and assembled by hand.

“I was thinking at the time, that Mark Zuckerberg was never hot gluing anything at Facebook – so maybe this is not a good idea,” recalls Chesky.

The founders sent boxes to hundreds of the most well-known tech bloggers, hoping that they would proudly display them on their desks and that they, or their colleagues, would eventually write their story. Shortly thereafter, they started selling the political cereal at $40 per box. The Obama O's sold like hot cakes, so much so that they had to give out Cap’n McCain's for free with each purchase.

— Pando

Slack

That was essentially our beta release, but we didn't want to call it a beta because then people would think that the service would be flaky or unreliable,” Butterfield says. Instead, with help from an impressive press blitz (based largely on the team's prior experience — i.e. use whatever you've got going for you), they welcomed people to request an invitation to try Slack. On the first day, 8,000 people did just that; and two weeks later, that number had grown to 15,000.

The big lesson here: Don't underestimate the power of traditional media when you launch.

Instagram

They also contacted the press directly rather than using a PR firm, and Kevin notes that this went down very well. A good product, pitched by the passionate creators themselves, and as it happens they secured a load of good coverage for launch. “We were shameless about contacting people who we thought would love the product”, says Kevin. “But it paid off. People actually said to us there’s no point contacting publications such as The New York Times and that we’d be wasting our time. But not only did The New York Times speak to us, they also sent someone to meet with us”. On the day of launch in October 2010, all the press coverage happened at roughly the same time and their servers were hit hard.

— TNW

7. Build a community pre-launch

Key question: Could you build a community now, to leverage later?

Product Hunt

Product Hunt, a daily leaderboard of new products, began as an email list using Linkydink, a tool for creating collaborative daily email digests. […]

Over Thanksgiving break, we designed and built Product Hunt. Meanwhile, we reached out to contributors in the MVP and other respected product people, sharing early mocks and gathering feedback. We weren’t just doing customer development, we were getting them excited and making them feel like part of the product (and they were, helping guide our design decisions).

5 days later, we had a very minimal but fully functional product. We emailed our supporters a link to Product Hunt, informing them not to share it publicly. The supporters were thrilled to join and play with a working version of something they had thought about and indirectly, helped build. That day we acquired our first 30 users. […]

By the end of the week, we had 100 users and felt ready to share Product Hunt with the world.

StackOverflow

The founders of Stack Overflow (Joel Spolsky & Jeff Atwood) both had large communities of existing followers from their previous online endeavors (Joel On Software and Coding Horror respectively). They invited members of those communities to participate in a private beta, in which they seeded the site with content so it didn't launch with no content whatsoever.

— Jon

In summary

Top seven strategies to acquire your first 1,000 users

Go where your target users are, offline

Go where your target users are, online

Invite your friends

Create FOMO in order to drive word-of-mouth

Leverage influencers

Get press

Build a community pre-launch

Key questions to ask yourself to determine where to focus:

Who are your early target users, and where they currently congregating, offline?

Who are your early target users, and where they currently congregating, online?

Do your friends fit into the target user group? If so, have you invited them yet?

Does your product rely on UGC? Consider curating the early community.

Is your value-prop incredibly strong? Consider throwing up a waitlist.

Is your product innately social? Consider relying on existing users to invite new users.

Who are influencers of your target users, and how could you get them to talk about your product?

What’s a unique, compelling, fresh story you could pitch press?

Could you build a community now, to leverage later?

That’s it for this week! Hit me up if you have any stories, feedback, or insights to share. Otherwise, see you next week!

Image sources: Tinder, DoorDash, Lyft, Robinhood, Twitter, Nextdoor, Etsy, Mailbox, Pinterest, Product Hunt, Airbnb

If you’re finding this newsletter valuable, consider sharing it with friends, or subscribing if you aren’t already.

Sincerely,

Lenny 👋